|

||||

|

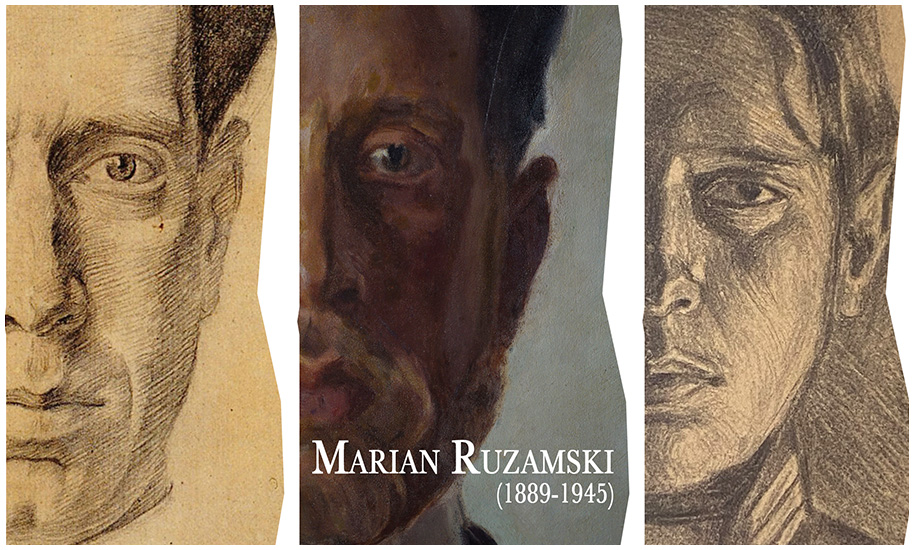

Marian Ruzamski (1889-1945)

Polish artist, painter aka. "Doctor Monster" KL Auschwitz prisoner no. 122843 >> home page |

Marian Ruzamski had enthusiastic reviews and exhibitions in the most important salons of the Second Polish Republic, but he never made his path to the elite of Polish painters of the 20th century. Why? by: Tadeusz Zych Marian Ruzamski was born on February 2, 1889 in Lipnik near Bielsko Biała, in a family with Polish-French-Jewish roots, which in 1891 changed its surname Mazur to Ruzamski. In 1903, the Ruzamskis moved to Tarnobrzeg, where Marian's father, Antoni, got a job as a notary public. Young Ruzamski showed his outstanding artistic talent already in his junior high school, successfully portraying his friends and teachers. Therefore it was not surprising that after graduating from the Kraków's Sobieski Gymnasium, he chose to study art, entering the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków in 1908, where he studied in the class of: Stanisła Dębicki, Leon Wyczółkowski, Jacek Malczewski and Julian Fałat. Simultaneously with exploring the secrets of art, he undertook the effort of supplementing his general knowledge by enrolling in the faculties of law and philosophy of the Jagiellonian University. Studying at the Kraków academy coincided with its reform, which meant that Marian received not only solid craftsmanship, but also a relatively large freedom in moving along the paths of art. Years later, in a letter to Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, he described the first period of his stay in Kraków: "In 1907 and 1908 I attended the National Museum and the Franciscan Church, where I took particular pleasure in copying works of Stanisław Wyspiański. It must've been similar to what you feel when translating other peoples' books to Polish [...] My copies were lost afterwards, but years later one surfaced as Wyspiański's original, and certified by experts as such"[1]. Ruzamski graduated from painting studies with a silver medal, and a year later, after winning a competition announced by the Society of Friends of Fine Arts in Kraków, he went to Paris, where he could stand "eye to eye" with the greatest works of great masters. Unfortunately, his stay in Paris was shorter than the artist had planned, because at the outbreak of the I World War, as a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, he had to leave the capital of France for fear of internment. He returned to Tarnobrzeg, from where at the end of 1914 he was taken by the Russian occupying forces withdrawing from the city. He spent the whole four long years of World War I as a "civilian prisoner of war" in Russia near Kharkiv. Here, for the first time in his life, he experienced genuine poverty, which he survived thanks to his painting talent. At the request of local residents, he painted portraits and flowers, which he then exchanged for food. An additional, truly traumatic experience was the painter's encounter with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Her cruelty and constant living in a state of extreme poverty eventually led him to a nervous breakdown. Memories of those years will accompany him throughout his life and will ensure that, despite the fact that in the 1930s he will live in a typically left-wing environment, he will never become an apologist for the Soviet system. After returning to Poland, where he managed to bring some of his works from the Kharkiv period, including the often reproduced oil portrait of "Bolshevik", Ruzamski stayed first in Kraków and then in Lwów, where he worked as an assistant to professors: Władysław Sadłowski and Jan Sas Zubrzycki at the Faculty of Architecture of the local University of Technology. The Kraków and Lwów periods are the best times in Ruzamski's work. The artist changed his approach, style and technique of painting, gradually moving away from oil paints in favor of pencil, pastels and especially watercolors. In the latter he became a true master, which was readily noted by the critics of the time. "Marian Ruzamski's watercolors," as one of the critics wrote, "are signs of an outstanding talent. The softness, airiness, impressionistic views of cities and landscapes are extremely difficult to paint with watercolors - and this is what constitutes artist's greatest achievement" (Jan Kleczyński). Another critic added: "Ruzamski is an artist about whom we can say that he has already found his expression. And this consists of a delicate drawing and a subtle, usually warm tone in bright color combinations, where the interaction of light, as if sifted, plays an outstanding role through the transparent muslin of pure mist"(E. Taurus). Frequent subjects of Ruzamski's works were panoramas of Kraków and Lwów, as well as portraits of people he knew. In his watercolours, you can exeprience a self-developed technique of applying paints to the ground previously moistened with water. This treatment allowed to achieve incredible effects, including the so-called "mists". His ability to look at the model's face is also astonishing, in which the artist was also able to convey the emotional state of the portrayed person. This painting genre evokes the idea of people creating paintings by his university masters: Fałat and Wyczółkowski. Ruzamski became close friends with the latter, hosting him in his home in Tarnobrzeg and organizing joint painting expeditions to the vicinity of Sandomierz. In a letter to the French magazine "La Revue Moderne", Ruzamski made his artistic self-assessment as follows: "Without considering myself a leading, representative figure in Polish art, I do my best to maintain a decent average level that I can afford [...] I am an amateur in art. I am not and have never been an avant-gardist. I profess traditionalism in art in the essential, non-superficial sense of the word. Value and color are my artistic means, not line. Among the artists closest to me I will mention: Turner, Daumier, Carriere, Zorn, Polish: Ślewiński, Krzyżanowski, Pankiewicz and Boznańska [...] My best paintings are completely unsuitable for photographic photos, because they are based on color, as the subject - views of Polish cities in the sun through fog or flowers. Also, portrait and landscape. As for techniques, I had previously abandoned oil, devoting myself exclusively to watercolor."[2] Ruzamski painted a lot during this time, he also exhibited a lot, often receiving enthusiastic reviews in the nationwide press "Portrait is becoming an area in which Ruzamski's talent is most fully expressed [...] in terms of characteristics, these portraits are unparalleled and there are few similar ones in contemporary Polish visual arts" - wrote Władysław Terlecki about Ruzamski's painting. In 1927, the artist also had his individual exhibition in Czech Prague. A year later he returned to Tarnobrzeg, where he settled permanently, consciously choosing the role of an artistic outsider. Away from large cultural centers, he created an artistic environment in a small town of four thousand people, which met in the house of doctor Eugeniusz Pawlas and his wife Janina, the so-called "Pawlasówka". The guests of Ruzamski and Pawlas were i.a. Emil Zegadłowicz, Stefan Żechowski, Stanisław Piętak, Andrzej Piwowarczyk. Years later, Stefan Żechowski recalled the artist from Tarnobrzeg: "He was an extraordinary man. His philosophical and painting views were characterized by deep humanism. He painted hundreds of pictures and made a lot of drawings. Despite these achievements, he remained almost unknown, because he did nothing to popularize his art. He was completely free from any need for publicity or fame"[3]. At the end of the 1920s, he once again made an attempt to enter the current of Kraków's art, becoming associated with the painter and sculptor Stanisław Szukalski and his group "The Tribe of the Horned Geart". Ruzamski knew Szukalski from the time of his studies at the Kraków's Academy and he considered his original, albeit very controversial, views on art as an opportunity to break the established and academic patterns in it. Cooperation with the Szukalski and his pupils even led Ruzamski to become the editor-in-chief of their magazine "Krak". He also published in 1934, at his own expense, a pamphlet entitled "Who is Szukalski?" being a kind of panegyric of an eccentric artist. However, in the mid-1930s their paths diverged, although Ruzamski will consider Szukalski the greatest artist until the end of his days. Apart from painting, his second passion was literature. Ruzamski's contacts with many writers (including Tuwim and Boy Żeleński) resulted in his own literary attempts. He wrote mainly epigrams and poems. Tuwim included some of them in his book "Four Centuries of Polish Epigrams". In the mid-1930s, the artist clearly shifted his political views to the left, which, among other things, led him to meet and become friends with Emil Zegadłowicz, who visited his house in Tarnobrzeg many times and with whom he had extensive correspondence for several years [4]. Ruzamski was also the official publisher of his scandalous book "Motory", illustrated by Stefan Żechowski at his instigation. Writer's thanked Ruzamski by including in his novel a story written by Ruzamski entitled "A History Lesson for Children in the Year 5047". Despite his fascination with literature, Ruzamski did not completely abandon painting. Although he created less and basically did not exhibit, his works focused on native themes, being a record of the extraordinary colors of small-town and multicultural reality. The war and the German occupation brought Ruzamski the experience of totalitarianism, second only to the Bolshevik one. He often expressed hois fears in letters to his friends. Huge poverty, on the one hand, and friendships, which proved itself in extreme conditions, on the other, marked the artist's wartime existence. Only selling his drawings in the villages of Zawiśle and the support of "the Kind Soul", as the artist used to call Janina Pawlasowa, saved Ruzamski and his friends from oppression. On the brink of April 4th, 1943, Ruzams was arrested, accused of Jewish descent and homosexuality, and transported to KL Auschwitz. He was denounced by the local Volksdeutsch, in revenge for the fact that the artist did not want to make a portrait of him. In Auschwitz he received the number 122843, as the last stage of Ruzamski's life and work began. Despite asrtist's poor health, thanks to help from his fellow prisoners, who nicknamed him the "Professor", food parcels from Janina Pawlasowa, and above all "an escape into art" he survived the following months of camp hell. In Auschwitz he met famous Polish sculptor Xawery Dunikowski. His last works were presented years lates at the great Berlin exhibition "Kunst in Auschwitz"[5]. Its curator, Jurgen Kaummketter, described these works: "The traditionalism of the artistic means of expression contained in the paintings and the simplicity in which the artist gave up everything that could distract the attention are particularly visible in the series of his portraits, their similarity to the portraits of Hans Holbein the Younger suggests itself"[6]. Miraculously saved, they are proof of the greatness of art, giving hope and the possibility of sheltering even from the worst evil. Marian Ruzamski did not live to see freedom, although he was only a days away from it. In early 1945, he was among the 60,000 prisoners who were evacuated by the Germans from KL Auschwitz. Walking through the so-called Death March, which half of the prisoners did not survive. In the first days of March 1945, extremely exhausted, dehydrated and freezing, Ruzamski reached the camp in Bergen Belsen, where he died on March 8, few weeks before the Allied troops liberated the camp. Throughout this murderous journey, Ruzamski carried with him what was most valuable to him - his camp drawings and watercolors, a total of 49 works that made up the so-called "Aschwitz File". After his death, one of his fellow prisoners took care of them and he transported them to France, from where they were returned, in accordance with the artist's last will, to his loved one - Janina Pawlasowa. Today, they reamain the property of the KL Auschwitz State Museum in Oświęcim. Completely forgotten after the war, he awaits rediscovery and the reinstatement to his rightful place in the history of 20th-century Polish painting. footnotes: >> home page |

|||